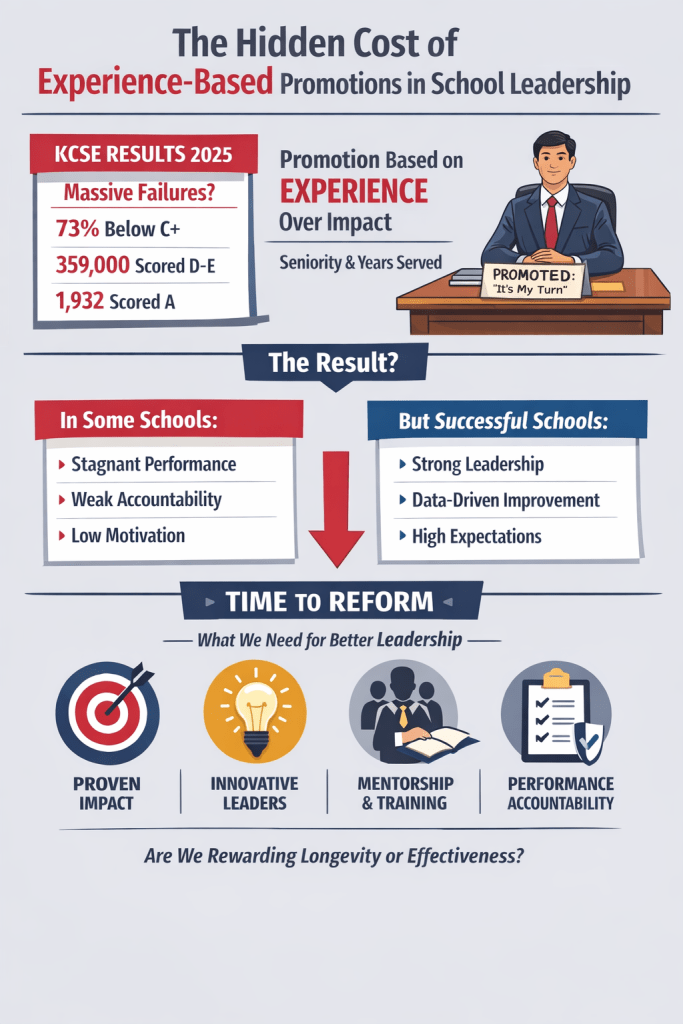

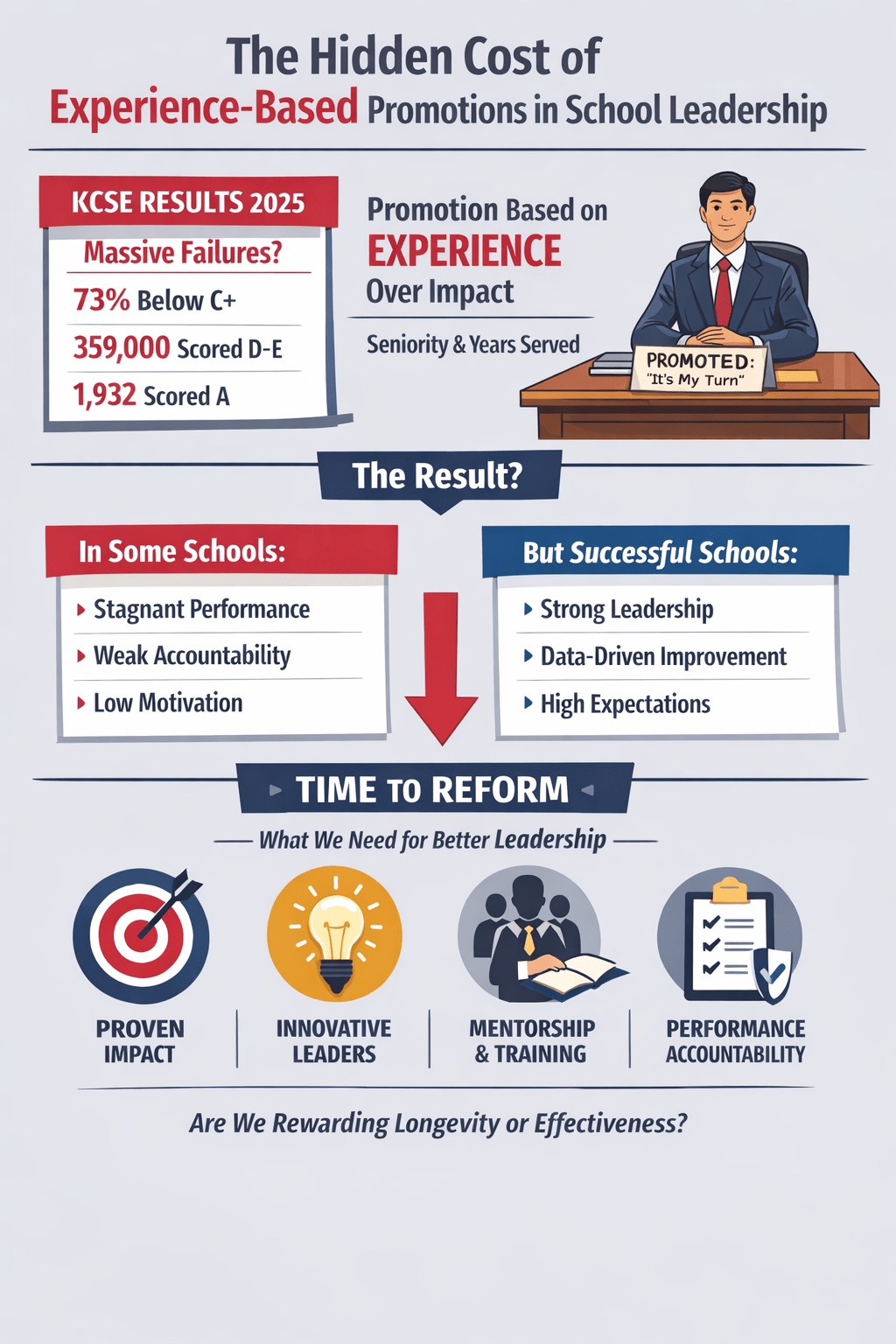

The release of the latest KCSE results has reignited a familiar national debate: Are Kenyan learners failing, or is the system failing them?

While attention has largely focused on curriculum changes, grading standards, and learner preparedness, one critical factor remains under-examined — school leadership succession and promotion practices under the Teachers Service Commission (TSC).

At the centre of this discussion is a sensitive but necessary question: Has TSC’s heavy reliance on experience as the primary criterion for promotion undermined performance in some schools?

Experience is Valuable but not Sufficient

There is no dispute that experience matters in education leadership. Years spent in the classroom and in school administration build institutional memory, professional maturity, and an understanding of learner dynamics. However, experience alone does not automatically translate into effective leadership.

In recent years, TSC’s promotion framework has leaned strongly toward, years of service, time spent in a particular job group, seniority and age.

While this approach offers administrative fairness and legal defensibility, it risks confusing longevity with leadership effectiveness.

The result, in some cases, has been the elevation of leaders who are competent administrators but weak instructional leaders. We have created individuals who can manage routines yet struggle to drive academic improvement.

Promotion or Entitlement?

In many schools, promotions are quietly perceived as a matter of “turn-taking.” Deputies in schools wait their time knowing that advancement is almost guaranteed once the required years are served. This mindset breeds what can be described as career-complete leadership. That is leaders who feel they have arrived, rather than leaders driven to transform.

When leadership is treated as a reward for endurance rather than responsibility for results, several consequences emerge.

These consequences include reduced urgency around curriculum coverage, weak teacher supervision and mentorship, minimal use of data to guide instruction, and tolerance of mediocrity disguised as stability

These are not dramatic failures. They are slow, cumulative declines, and KCSE results are often the first public signal that something has gone wrong.

KCSE Results as a Leadership Mirror

National examinations are lagging indicators. A school’s KCSE performance reflects leadership decisions made three to five years earlier.

These decisions include staffing choices, subject support strategies, teacher motivation, and academic culture.

The persistent pattern seen in many underperforming schools is not a lack of learner effort, but inconsistent academic focus, poor instructional leadership, and limited innovation in teaching strategies

Conversely, schools that outperform their resource levels often share one feature: strong, hands-on leadership, regardless of the leader’s age or years of service.

Principals in schools that performs are visible in classrooms, hold teachers accountable, analyse performance data, and cultivate a culture of high expectations. Notably, many are not the most senior teachers, but they are the most effective leaders.

The Succession Problem

An experience-heavy promotion model weakens succession management in three ways:

• It discourages excellence. Talented deputies and teachers quickly learn that innovation and results do not accelerate progression.

• It undermines mentorship. When promotion is time-based, leaders feel less pressure to groom successors or transfer skills.

• It freezes leadership culture. Schools wait for leadership change rather than building leadership capacity internally. Over time, this erodes academic ambition and affects learner outcomes.

A Fair but Flawed System

It is important to acknowledge TSC’s constraints. Managing promotions for tens of thousands of teachers nationally requires clear, verifiable criteria.

Experience is easy to measure, difficult to contest, and politically safer than subjective assessments of performance.

However, what is administratively convenient is not always educationally effective.

To its credit, TSC has recently moved toward higher qualification requirements and performance contracting. Yet without tying promotions more closely to demonstrated school improvement, these reforms risk becoming cosmetic.

Toward a Balanced Promotion Framework

Experience should remain a pillar — but not the sole pillar — of leadership advancement. A more effective succession and promotion model would balance:

• Years of service

• Demonstrated improvement in school performance

• Instructional leadership competence

• Teacher mentorship and staff development outcomes

• Evidence-based decision-making

In short, promotion should reward impact, not just endurance.

Conclusion

The KCSE results should not be read simply as evidence of learner failure. They are also a reflection of leadership systems, policies, and succession choices made over time.

Where leadership is dynamic, accountable, and learner-focused, results tend to improve — even under difficult conditions. Where leadership is passive, entitlement-based, and insulated from performance scrutiny, outcomes stagnate.

If Kenya is serious about improving learning outcomes, school leadership succession must move beyond experience as a proxy for excellence. The future of school performance depends not only on what happens in classrooms, but on who leads them — and why they were chosen.

#KCSE2025 #EducationLeadership #SchoolManagement #TSC #SuccessionPlanning #EducationReform #LeadershipMatters

Dr. John Chegenye is a Human Resource Management scholar, educator, and consultant specializing in organizational behavior, labor relations, and performance management. He writes on leadership, labor policy, and institutional development.

Leave a comment