Education in Kenya is constitutionally guaranteed and politically celebrated as “free.” Yet for millions of households, educating a child has become one of the most financially stressful responsibilities they face. From primary school to university, the gap between policy promises and lived reality continues to widen, pushing many families to the brink and, in some cases, out of the education system altogether.

This crisis is not caused by one factor. It is the cumulative result of underfunding, rising household costs, policy blind spots, and a failure to confront the real drivers of school expenses — particularly in day secondary education.

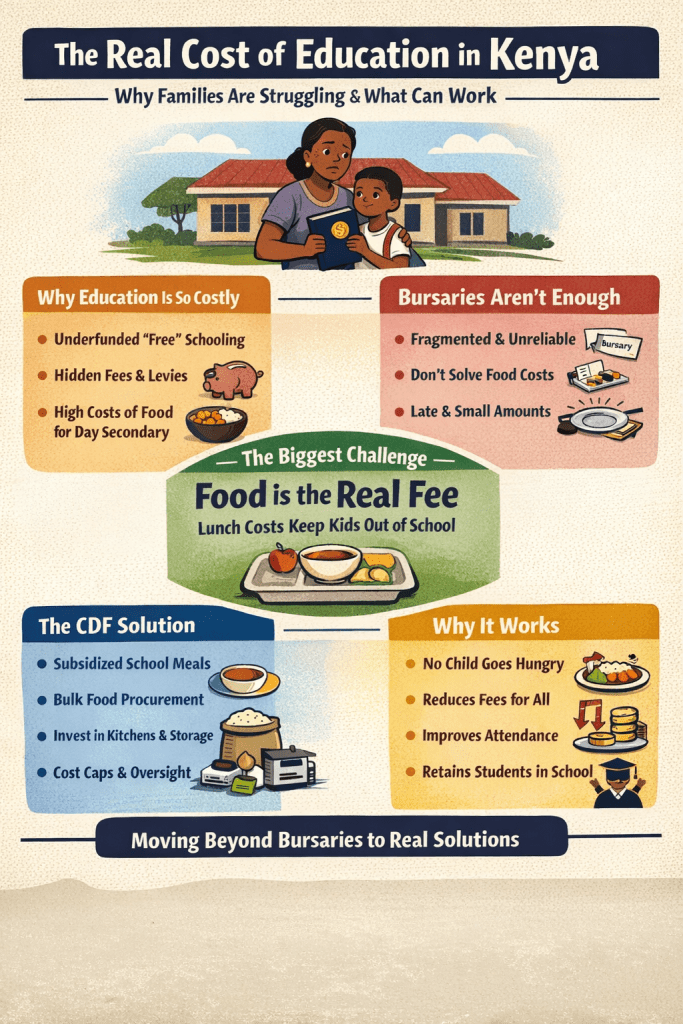

Why Education Has Become So Expensive

Several reasons suffice:

1. Underfunded and Unpredictable “Free” Education

Kenya’s Free Primary Education (FPE) and Free Day Secondary Education (FDSE) programmes rely on government capitation to schools. Over time, this funding has become inadequate, delayed, and occasionally reduced. Schools receive less than what is required to meet operational costs, and often receive it late.

To survive, schools quietly transfer these costs to parents through:

• Development levies

• Activity and exam charges

• Remedial and tuition fees

• Food and utility costs

The result is a system that is free in law but expensive in practice.

2. The Hidden Costs That Parents Actually Pay

For most families, school expenses are no longer dominated by tuition. Instead, they are driven by:

• Uniforms and learning materials

• Transport

• Examination-related charges

• Food, especially in day secondary schools

It is food — not tuition — that has quietly become the biggest and most persistent cost driver for parents with children in day secondary schools.

Why Many Kenyans can no Longer Educate their Children

Household incomes have not kept pace with inflation or rising education-related costs. Parents are forced to choose between essentials: food, rent, healthcare, or school expenses.

For day secondary learners, hunger directly affects attendance, concentration, and retention. Some learners skip school on days they cannot afford lunch. Others drop out entirely.

Girls, learners from informal settlements, and children from arid and semi-arid regions are disproportionately affected.

The Failure of Bursaries as a Solution

Bursaries are the government’s and politicians’ most common response to education costs. But bursaries are increasingly ineffective.

Bursaries fail because:

• They are fragmented and unpredictable

• They individualise a systemic problem

• They often arrive late or in small amounts

• They do not reduce the underlying cost structure

Most importantly, bursaries do not solve the food problem. Even when a child receives a bursary, schools still charge food levies. Hunger remains.

The Overlooked Truth: Food Is the Real Fee in Day Secondary

In day secondary education, tuition may be subsidised — but lunch is not. For schools, feeding students is unavoidable. For parents, it is non-negotiable. For learners, it determines attendance and performance.

Treating food as a private parental responsibility in a public education system has created a silent crisis. Hunger has become the hidden gatekeeper of access to education.

What CDF can do to Mitigate the Situation

Recent constituency-level interventions, notably in Kiharu constituency, by MP Ndindi Nyoro, reveal an important lesson: system-level solutions work better than individual handouts.

Instead of expanding bursaries, Constituency Development Fund (CDF) resources can be used to lower the cost of education for everyone.

How?

1. Constituency-wide school feeding subsidies

CDF can centrally procure staple foods (maize, beans, rice, cooking oil) and distribute them directly to day secondary schools. This immediately reduces or eliminates food levies charged to parents.

2. Bulk procurement to lower unit costs

Buying food at constituency level cuts out middlemen, stabilises prices, and can reduce food costs by 30–40% without increasing budgets.

3. One-time infrastructure investment.

CDF can fund energy-efficient kitchens, water harvesting, and food storage facilities. These reduce recurring costs and stop schools from passing fuel and utility costs to parents.

4. Cost caps and accountability agreements.

Schools receiving food support can be required to cap or eliminate lunch charges, with transparent costing shared with parents.

5. Retention-focused targeting

Feeding programmes can prioritise Forms 1–3, where dropout risk is highest, turning food support into a retention and performance strategy.

Why this Approach Works Better than Bursaries

• It removes stigma. Everyone eats

• It is easier to audit — food delivered, not cash issued

• Parents feel relief daily, not once per term

• Schools stop chasing food fees

• Learners attend, concentrate, and perform better

• Politically and socially, it builds trust. Administratively, it is cleaner. Educationally, it works.

What the National Government Must Confront

Kenya’s education financing debate must move beyond tuition. If food is now the main barrier to access in day secondary education, then:

• Free education cannot be declared without addressing meals

• Capitation must reflect real costs

• School feeding must be treated as an education input, not a welfare add-on

• CDF innovations should inform national policy

Conclusion

The cost of education crisis in Kenya is not abstract. It is lived daily by parents deciding whether their children will eat or learn. Bursaries, while well-intentioned, are no longer sufficient. The real pressure point — food — requires collective, system-level solutions.

CDF has shown that when resources are used to reduce shared costs rather than patch individual hardship, education becomes truly accessible. The question now is whether national policy will catch up with this reality — or continue to pretend that “free education” exists while hunger keeps children out of school.

Leave a comment