Introduction

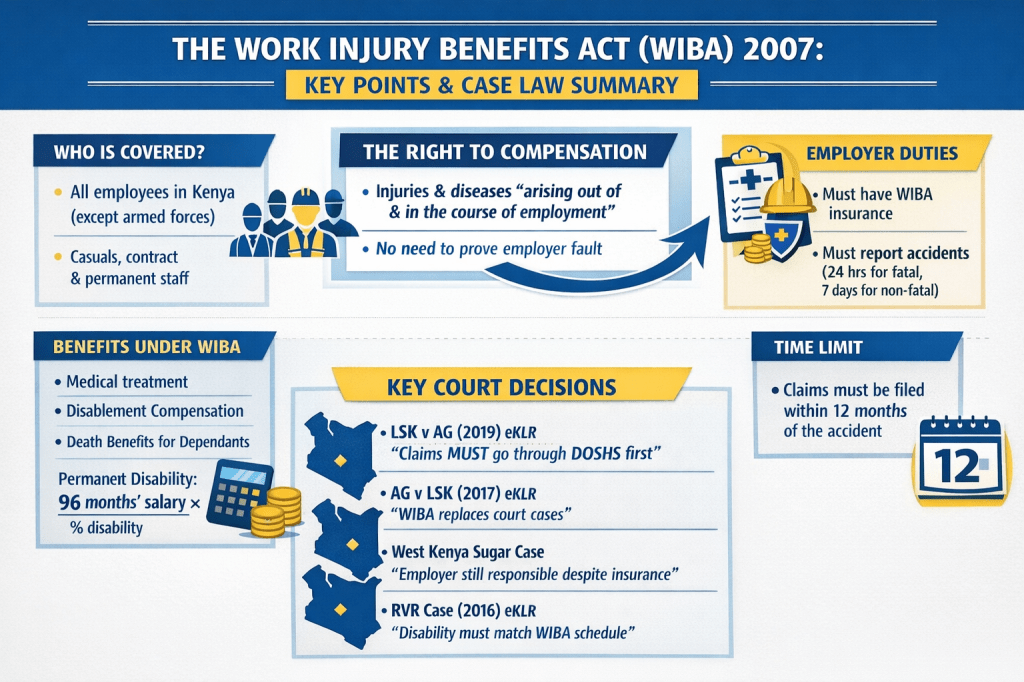

Workplace injuries are an unavoidable reality in Kenya’s labour market, cutting across construction sites, farms, factories, transport services, offices, and the public sector. The legal issue is therefore not whether accidents occur, but how injured workers are compensated. The Work Injury Benefits Act (WIBA), 2007 was enacted to provide a structured, predictable, and non-adversarial system for compensating employees injured in the course of employment.

WIBA replaced the former Workmen’s Compensation Act and shifted work injury claims from fault-based court litigation to an administrative compensation framework under the Directorate of Occupational Safety and Health Services (DOSHS). This shift has since been affirmed and clarified by Kenya’s superior courts.

The Right to Compensation Under WIBA

Section 10(1) of WIBA provides that “an employee who suffers an injury or dies as a result of an accident arising out of and in the course of employment shall be entitled to compensation.” This provision establishes compensation as a statutory right rather than a discretionary benefit.

Importantly, the Act does not require an employee to prove negligence on the part of the employer. The focus is on whether the injury is work-related. Kenyan courts have affirmed that this framework deliberately removes fault from compensation claims in order to ensure efficiency and certainty, a position endorsed by the Court of Appeal and later affirmed by the Supreme Court in Law Society of Kenya v Attorney General (2019) eKLR.

Scope of Application: Who Is Covered

Under Section 3, WIBA applies to all employees in Kenya, whether engaged in the public or private sector, with the express exclusion of members of the armed forces. The broad wording reflects Parliament’s intention to extend protection to workers regardless of the nature or duration of their employment.

Courts have consistently rejected attempts to exclude casual or contract workers from the Act’s protection, emphasizing the existence of an employment relationship rather than contractual labels. This approach aligns with the constitutional principles of fair labour practices under Article 41 of the Constitution.

Work Injuries and Occupational Diseases

WIBA defines compensable injuries as those arising “out of and in the course of employment.” Section 38 extends this protection to occupational diseases, deeming them to be injuries caused by accidents.

This provision is particularly relevant in sectors such as agriculture, manufacturing, mining, and transport, where harm may develop over time. Courts have accepted that gradual injuries linked to workplace exposure fall squarely within WIBA’s compensation regime, provided medical evidence establishes a causal connection.

Absence of Fault and Employer Liability

A defining feature of WIBA is that it removes the need to establish employer negligence. Section 10 imposes liability based on the occurrence of a work-related injury alone, subject to limited statutory exclusions such as willful misconduct.

This no-fault structure was central to the constitutional challenge against WIBA. In Attorney General v Law Society of Kenya (2017) eKLR, the Court of Appeal held that Parliament was entitled to replace common-law negligence claims with a statutory compensation system.

The Supreme Court later affirmed this position, confirming that WIBA lawfully limits the role of ordinary courts in favour of administrative adjudication.

Mandatory Insurance and Employer Obligations

Section 7 of the Act imposes a mandatory obligation on employers to obtain insurance to cover liability under WIBA. This requirement is absolute and does not depend on the size or nature of the business.

Kenyan courts have clarified that insurance does not transfer statutory responsibility away from the employer. Even where an insurer is involved, the employer remains responsible for accident reporting, cooperation with investigations, and facilitation of compensation.

This position has been reiterated in several Employment and Labour Relations Court decisions following the Supreme Court ruling.

Reporting of Accidents

Section 21 requires employers to report fatal workplace accidents within twenty-four hours and non-fatal accidents within seven days. Failure to comply constitutes an offence under the Act.

Judicial decisions interpreting this provision have emphasized that reporting obligations are mandatory and not subject to managerial discretion.

Delayed reporting has been cited by courts as evidence of statutory non-compliance, exposing employers to penalties and undermining their position in compensation disputes.

Benefits Available Under WIBA

Sections 23 to 26 outline the benefits payable under the Act. These include medical treatment, temporary disablement benefits, permanent disablement compensation, and death benefits for dependants.

Temporary total disablement benefits under Section 28 are payable where an employee is incapacitated for more than three days and are limited to a maximum period of twelve months.

Courts have upheld this statutory cap, noting that it reflects Parliament’s balancing of employee protection with sustainability of the compensation scheme.

Permanent Disablement and Compensation Formula

Section 30 provides that compensation for permanent disablement is calculated based on ninety-six months’ earnings, adjusted according to the degree of disability assessed using the First Schedule.

Courts have stressed that disability assessments must be conducted by qualified medical practitioners and must correspond with the statutory schedule.

In Rift Valley Railways (Kenya) Ltd v Hawkins Wagunza Musonye (2016) eKLR, the court emphasized that compensation awards must strictly adhere to the percentages prescribed in the First Schedule to maintain consistency and predictability.

Death Benefits and Dependants

Where an employee dies as a result of a work injury, Section 25 and the Third Schedule govern compensation to dependants.

The Act prescribes percentages payable depending on the number and status of dependants, alongside funeral expenses.

Judicial interpretation has reinforced that these benefits are statutory entitlements and not subject to employer discretion.

Courts have rejected attempts to substitute ex-gratia payments for legally prescribed compensation.

Limitation Periods and Procedural Compliance

Section 26 requires claims to be lodged within twelve months of the accident or death. Kenyan courts have treated this limitation period as mandatory, subject only to narrow exceptions.

In Mumias Sugar Company Ltd v Francis Wanalo (2018) eKLR, the court affirmed that failure to comply with statutory timelines may defeat a claim, underscoring the importance of procedural discipline under WIBA.

Jurisdiction and the Role of Courts

Perhaps the most significant judicial clarification relates to jurisdiction. Section 16 of WIBA assigns primary jurisdiction over work injury claims to the Director of Work Injury Benefits. This provision was upheld by the Supreme Court in Law Society of Kenya v Attorney General (2019) eKLR.

The Court held that claims arising after the commencement of WIBA on 2 June 2008 must be processed administratively, with appeals lying to the Employment and Labour Relations Court.

Ordinary civil courts lack original jurisdiction in such matters, except where claims were already pending before WIBA came into force.

Conclusion

When read together with judicial interpretation, the Work Injury Benefits Act, 2007 emerges as a comprehensive social protection framework grounded in efficiency, certainty, and fairness. Kenyan courts have consistently affirmed its constitutionality, mandatory nature, and administrative structure.

For employers, compliance requires insurance, reporting systems, and procedural vigilance. For employees, awareness of rights, timelines, and compensation mechanisms is critical. Ultimately, WIBA reflects a deliberate policy choice: to prioritize compensation over blame and administrative justice over prolonged litigation.

#WIBA #WorkInjuryBenefitsAct #KenyaLabourLaw #HumanResourceManagement #WorkplaceSafety #HRCompliance #EmploymentLaw #OccupationalSafety #DOSHS #Kenya

Dr. John Chegenye is a Human Resource Management scholar, educator, and consultant specializing in organizational behavior, labor relations, and performance management. He writes on leadership, labor policy, and institutional development.

You can also follow our YouTube Channel for related Videos @john_chegenye

Leave a comment