Introduction

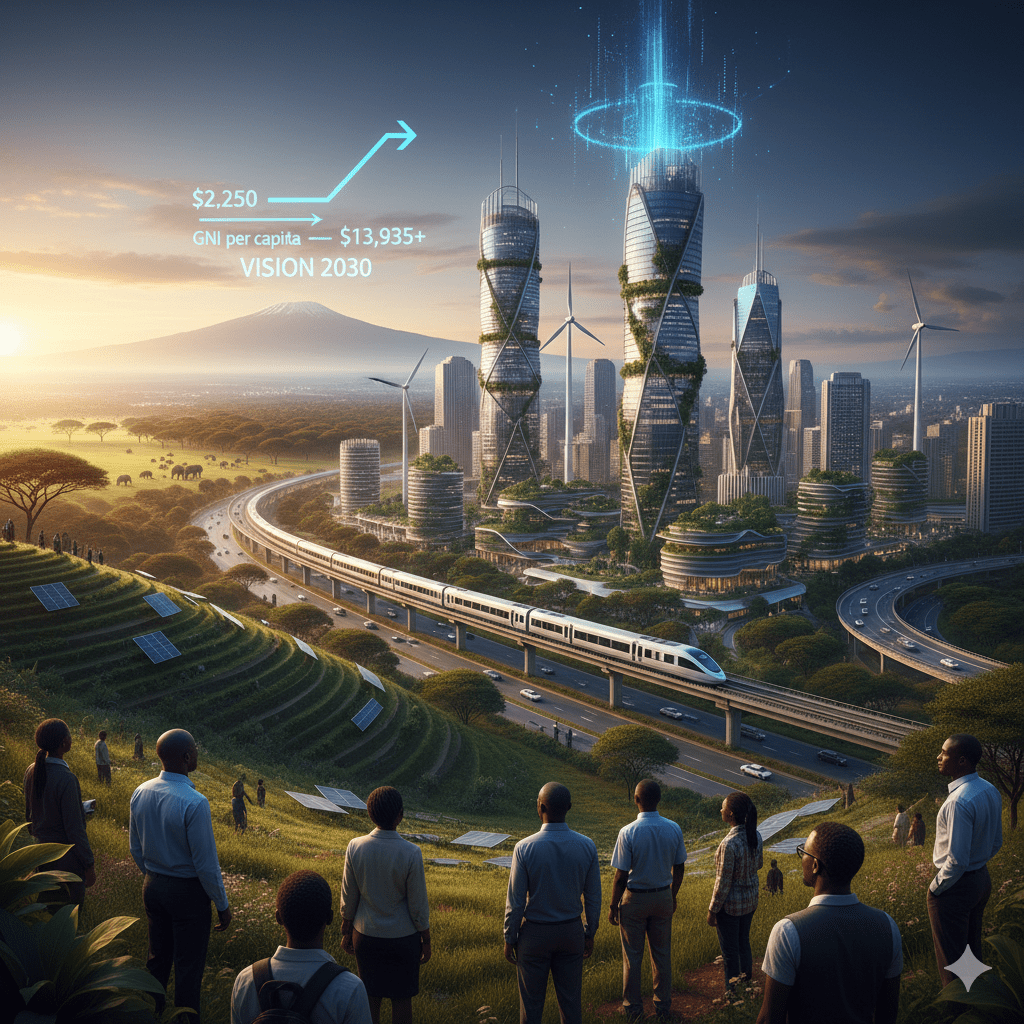

Kenya has set an ambitious national goal. It intents to transition from its current Lower-Middle-Income status to a high-income, industrialized, and globally competitive economy. This aspiration has been articulated in the President’s blueprints and conjoined into the Bottom-Up Economic Transformation Agenda (BETA). Being a proposed plan it requires more than just incremental growth; it demands a “Giant Leap” fueled by profound, disciplined policy reform and economic restructuring.

1. Defining the Challenge: The Gap and the Paradox

The aspiration to become a “Developed Nation” is correlated with achieving the World Bank’s High-Income Economy classification, which is based on Gross National Income (GNI) per capita.

The Quantitative Benchmark

As of the latest classifications (using 2024 data for the World Bank’s Fiscal Year 2026), a country must achieve a GNI per capita of US$13,935 or more to be considered a High-Income economy (Source 1). This figure serves as the critical, quantifiable hurdle Kenya must clear.

The Paradox of Economic Growth and Increasing Poverty

Kenya is currently categorized as a Lower-Middle-Income country, with a GNI per capita estimated to be around US$2,250 (Source 2). The chasm between the current figure and the High-Income threshold highlights the sheer scale of the required transformation. To bridge this gap, policy interventions must not only generate growth but must fundamentally shift the sources of income from low-productivity sectors to high-value, high-productivity activities.

The challenge is complicated by the simultaneous occurrence of national economic growth and widespread personal impoverishment, a concept known as decoupling. In decoupling, the benefits of expansion in an economy doesn’t trickle down to the majority of the population.

Another challenge is called Jobless growth paradox. In Jobless growth paradox concept, the national GDP can increase, but the benefits are concentrated in capital-intensive sectors like finance and large-scale infrastructure. These sectors can experience expansion but generally create few opportunities for the masses. The resultant effects is a situation of stagnant or declining real wages for the majority, widening inequality, and failing to translate economic expansion into widespread poverty reduction.

Oxfam Kenya (2025) in a report titled Kenya’s Inequality Crisis: The Great Economic Divide (Nov 2025), confirms these concepts discussed. The report posts that nearly half of Kenya’s population now lives in extreme poverty. They subsist on less than KSh 130 ($1) per day. The report illustrate that since 2015, the number of people in extreme poverty has increased by 7 million; a rise of about 37%.

The report continues that a tiny economic elite (about 125 richest Kenyans) has amassed enormous wealth and now own more wealth than some 42–43 million people combined (more than three-quarters of the population). The report further illustrate that CEOs of the ten largest companies in Kenya earn on average 214 times more than a teacher.

It therefore follows that a fundamental change in the economy’s output structure and its distribution mechanisms need reforms if we truly aspire the first world Status.

We need first to change from relying solely on aggregate economic indicators, such as Gross Domestic Product (GDP), to gauge the true welfare of a nation’s populace. The flaws in relying entirely on these parameters include:

1. Income Inequality and Wealth Concentration

The most significant factor in using GDP is severe income inequality. Economic growth is measured by the total value of goods and services produced, but this metric does not track who receives the resulting income. This leads to:

• The Rise of the Top: In many stable economies, the profits and productivity gains generated by growth are disproportionately captured by a small, wealthy elite, typically through capital ownership (stocks, bonds, real estate) and extremely high executive compensation.

• Stagnant Wages: While productivity per worker may increase due to technology or efficiency, real wages for the median worker often remain stagnant or rise only marginally. This means the workers are producing more value, but receiving a smaller share of it, leading to a decline in their real purchasing power, especially when combined with inflation.

2. Jobless or Low-Wage Growth

Economic growth can be driven by factors that do not require hiring more workers or paying them higher wages, creating a situation called jobless growth. These situations are found in:

• Automation and Technology: Advances in technology, particularly robotics and artificial intelligence, allow companies to increase output (boosting GDP) without increasing their workforce. Jobs that are created are often highly specialized (and highly paid) or low-skill, temporary “gig” jobs with limited benefits, leading to a rise in underemployment and a less secure income for the average person.

• Globalization and Outsourcing: When a country’s growth relies on the output of goods produced cheaply overseas (outsourcing production) or the sale of financial services and high-tech intellectual property, the physical production jobs that once supported the working class disappear or become low-paying.

3. The Limitations of GDP

GDP is a measure of total economic activity, not quality of life or income distribution. A high GDP can mask serious underlying problems:

• Failure to Reflect Costs: GDP treats all spending equally. For example, a massive expenditure on cleaning up an environmental disaster or on expensive private healthcare both count as positive contributions to GDP, even though they represent a cost or a loss of welfare for the population.

• Exclusion of Non-Market Activity: GDP ignores unpaid domestic labor, volunteer work, and the value of leisure, which are all critical to a community’s well-being.

• Population Growth: If GDP grows at the same rate as the population, GDP per capita remains flat, meaning the average person’s economic standing hasn’t improved. If population growth outpaces the growth in high-quality employment, the per capita wealth may increase, but the absolute number of people in poverty rises.

The Three Pillars of Transformation

Achieving the high-income threshold that can translate into prosperity for all requires simultaneous, multi-sectoral reforms centered around three key pillars:

Pillar A: Investing in Human Capital and Skills

Sustained high-income status is impossible without a highly educated and skilled workforce. The focus must shift from simply increasing enrollment to prioritizing relevance and quality.

• STEM Focus: Massive, targeted investment in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) education across all levels.

• TVET Modernization: Reforming and resourcing Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) institutions to align curriculum directly with the demands of modern industry (manufacturing, digital services, and advanced agriculture).

• Health and Nutrition: Ensuring a healthy, productive population through universal access to quality healthcare, as disease burdens directly impact productivity and human capital formation.

Pillar B: Unleashing Productivity through Competition

The primary driver of the GNI per capita gap is low productivity, often stifled by monopolistic structures, high operating costs, and bureaucratic friction. Pro-competitive reforms are essential for rapid output growth.

• Infrastructure & Energy: Reducing the cost of key inputs, particularly electricity, through deregulation, new generation capacity, and modernizing transmission.

• Agriculture Commercialization: Shifting farming from subsistence to commercial scale, integrating technology, and improving access to global value chains.

• Digital Economy: Deepening competition in the telecommunications and digital services sector to ensure low-cost access to the foundational tools of modern commerce for all citizens.

Pillar C: Fiscal Discipline and Structural Reform

The transformation must be financed responsibly while ensuring the benefits are inclusive and sustainable.

• Progressive Taxation: Implementing fair, progressive tax reforms to expand the revenue base without stifling nascent businesses, ensuring the wealthy and high-income earners contribute proportionally.

• Fiscal Consolidation: Instituting disciplined expenditure management to reduce wasteful spending and allocate resources to high-return investments (infrastructure, education, health). The massive national debt must be managed through responsible borrowing and clear debt servicing strategies.

• Governance and Anti-Corruption: Systematically tackling corruption and improving institutional governance to ensure public resources are used efficiently and predictably, which is vital for attracting high-value foreign direct investment (FDI).

Conclusion

The High-Income dream for Kenya is not an arbitrary aspiration but a defined, quantitative target that requires a GNI per capita nearly seven times its current level. This transition necessitates an uncompromising commitment to the three pillars of reform—Human Capital, Competition, and Fiscal Discipline. Success hinges on the political will to execute these difficult structural changes inclusively, ensuring that the benefits of rapid growth are shared across the entire population.

References

• World Bank. (2024). New World Bank country classifications by income level: 2024–2025. (Source: World Bank data on GNI per capita thresholds)

• World Bank. (Latest available data). GNI per capita, Atlas method (current US$). Kenya Data. (Source: World Bank public country data)

• Government of Kenya.Vision 2030 and Bottom-Up Economic Transformation Agenda (BETA) Policy Documents. (Source: Government policy literature)

By Dr. John Chegenye, Ph.D.; CHRP-K

Educator, Researcher, and Human Resource Management Specialist.

Leave a comment