Introduction

The relationship between the National Police Service Commission (NPSC) and the National Police Service (NPS) has recently been marked by conflict over roles in recruitment, promotion, discipline, and deployment. Here I will examines the dispute through a Human Resource Management (HRM) lens, compare the NPSC structure with other commissions like the Teachers Service Commission (TSC) and the Public Service Commission (PSC), and proposes an ideal governance framework that can harmonise HRM functions with policing operational needs.

First, i will start by noting that Human Resource Management in the public-sector policing requires a fine balance between professional autonomy, constitutional mandates, and operational efficiency. However, this balance is challenged by overlapping responsibilities between the NPSC and the office of the Inspector General (IG). The result has been recurring disputes touching on recruitment, promotions, transfers, payroll control, and disciplinary authority.

Understanding this contest requires analysing the structural design of the NPS, the constitutional frameworks guiding HRM in the public sector, and the operational realities of policing.

1. Structure of the National Police Service (NPS)

The NPS comprises three primary components:

1. Kenya Police Service (KPS)

2. Administration Police Service (APS)

3. Directorate of Criminal Investigations (DCI)

At the apex is the Inspector General (IG). The UG is the operational head of the NPS. The IG has constitutional independence in command, control, deployment, and day-to-day discipline.

Parallel to this structure is the National Police Service Commission (NPSC). NPSC is a constitutional commission mandated to manage recruitment, promotions, discipline, transfers, and human resource policy.

In design, this creates a dual-authority system: the NPSC has the HRM authority, while the IG/NPS has the operational authority

The challenge arises where HRM decisions affect command, and where command decisions influence HRM processes.

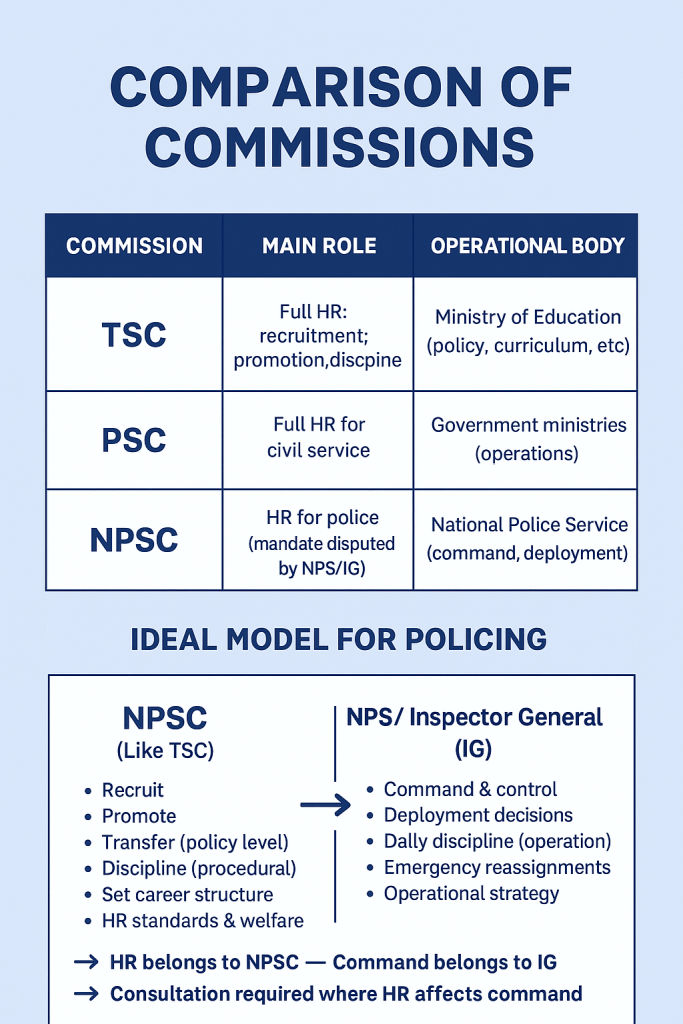

3. Comparing NPSC With other Commissions

This comparison will provide lessons for HRM clarity

Teachers Service Commission (TSC)

TSC operations look like the gold standard of HRM clarity in Kenya. It handles all HR functions for teachers. The Ministry of Education on the other hand handles policy and curriculum. Although there has been some conflicts there has been no serious competition in roles, hence no structural conflict.

Public Service Commission (PSC)

PSC manages HR for civil servants while ministries manage operations. In this structure the Commission handles HR while the Ministry/agency deals with operations.

What Makes NPSC Different from other Commissions?

Unlike TSC or PSC, the NPSC’s operational partner, the NPS, is led by the IG, who holds constitutional operational independence. Policing also requires rapid deployment, emergency relocations, and strict command chains.

Thus, unlike TSC, HR decisions in policing directly influence operational efficiency, making traditional HRM boundaries less straightforward.

Nature of the NPSC–IG Conflict: An HRM Analysis

1. HRM vs. Operational Control

The conflict between the NPSC and IG is fundamentally an HRM–operations clash:

– The NPSC argues that HRM must remain professional, independent, and insulated from internal command politics.

– The IG argues that staffing, transfers, promotions, and discipline directly affect field command and therefore cannot be isolated from operations.

2. The Core HRM Issues at Stake

a. Recruitment – Who runs recruitment? Who determines staffing needs?

b. Promotions – Who decides career progression?

c. Transfers – Are they HR moves or operational deployments?

d. Discipline – What constitutes a disciplinary offence vs. an operational breach?

e. Performance Management – Who evaluates officers, and how is merit established?

These are classic HRM functions, but in policing they are intertwined with security operations. This is what leads to the tension.

The Ideal HRM Framework for Policing: Lessons from other Commissions

From an HRM perspective, the ideal system is one where:

1 NPSC Holds Full HRM Authority

Just like TSC:

– Recruitment

– Promotions

– Transfers (policy level)

– Career development

– HR standards and welfare

– Major disciplinary processes

This ensures professionalism, fairness, and insulation from political or command interference.

2 The IG Holds Full Operational Authority

Including:

– Daily deployment

– Emergency reassignments

– Command and control

– Operational discipline

– Tactical management

This ensures operational readiness and responsiveness.

3 Joint HR–Operations Coordination Mechanism

This is the missing link today. There is need to constitute a formal committee that will be backed by law to oversee:

– Transfer requests

– Promotion recommendations

– Staffing forecasts

– Deployment impact assessments

– Disciplinary case referrals

This will mirrors how other sectors harmonise HRM and operations.

Hitting the Rock! Should the IG be made the CEO of NPSC?

I think not. The HRM Reasoning behind this is that HRM must remain independent to prevent abuse of power, internal favouritism, or politically motivated staffing. Making the IG the CEO would collapse HRM into operations, removing the checks and balances intended by the Constitution. It will be equivalent to making the Chief of Defence Forces the head of PSC. This will compound a structural contradiction.

The best practice is to keep the IG and NPSC separate, but create structured, binding consultation rules so neither can operate unilaterally where mandates intersect.

To do this we need very limited Law Reforms in a HRM View. This legal reform need not be constitutional amendments. What is required are:

1. Amendments to the NPSC Act and NPS Act to clarify on;

• definitions of “transfer”, “deployment”, “promotion”, and “discipline, and

• What is purely HRM vs what is purely operational

• How consultations must occur

2. Harmonised Regulations. Both Acts were developed separately and have contradictory sections. A harmonised regulatory framework is needed.

3. Establishing a Statutory Coordination Mechanism

A joint HR–Operations board would end disputes permanently.

Conclusion

From an HRM perspective, the conflict between NPSC and the IG is not simply a power struggle. it is a structural design issue rooted in unclear boundaries between HRM and operational command. Benchmarking best principles used elsewhere can create a policing system where:

– HRM is professional, fair, and independent.

– Operational command remains responsive and autonomous.

– Consultation bridges the two functions.

– use legal clarity to eliminate institutional rivalry.

This HRM-based approach offers the most sustainable path to resolving the NPSC–IG dispute and strengthening police governance in Kenya.

By Dr. John Chegenye, Ph.D.

Educator, Researcher, and Human Resource Management Specialist.

Leave a comment