By Dr. John Chegenye

The ongoing dispute between university unions and the Ministry of Education over the contested salary increment balance as advised by the Salaries and Remuneration Commission (SRC) once again has exposed the fragile state of industrial relations in Kenya. While the SRC’s constitutional mandate is to regulate remuneration in the public sector, its advisory to the ministry appears to have triggered renewed mistrust and frustration among unions in Kenya, particularly the Universities Academic Staff Union (UASU), who argue that SRC advise does not reflect the reality of the negotiated Collective Bargaining Agreements (CBAs).

A Mandate Rooted in Fiscal Prudence

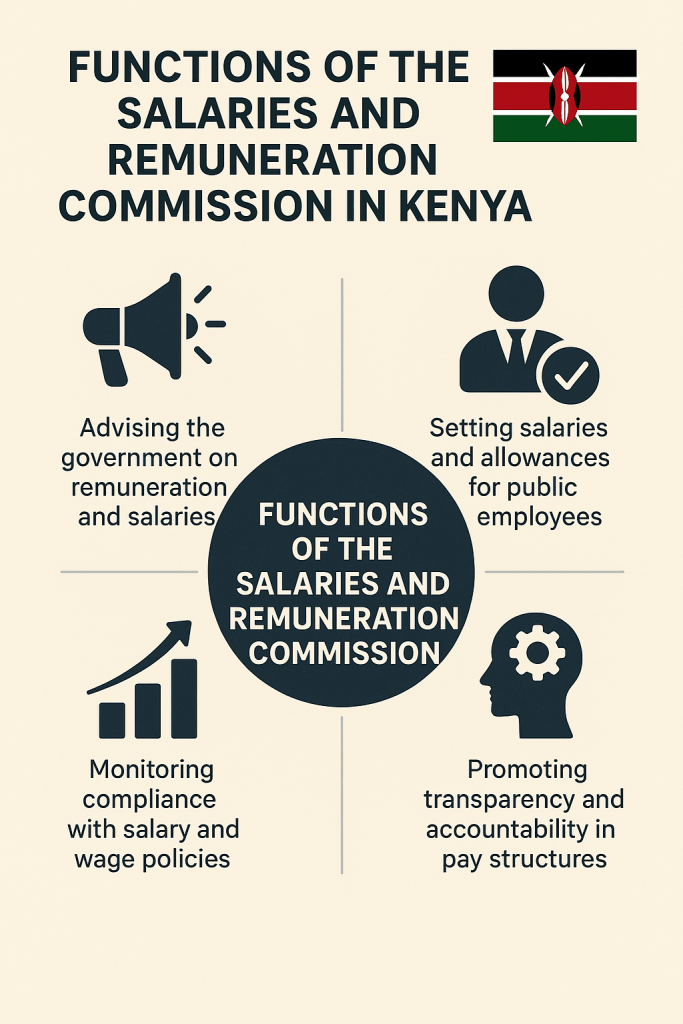

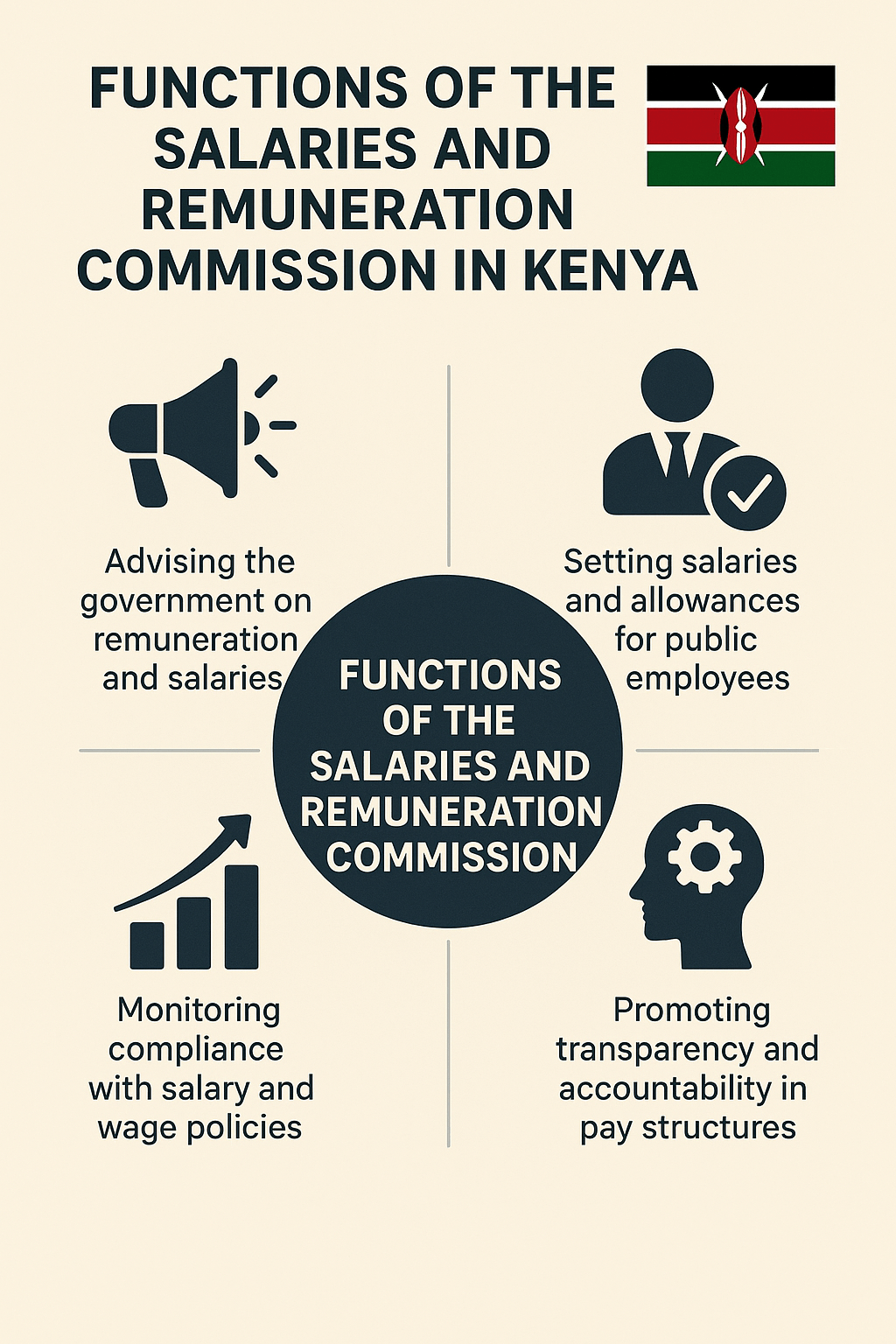

The SRC was established under Article 230 of the Constitution to ensure equity, fairness, and fiscal sustainability in public service pay. In principle, this is an indispensable role. It is evident that the establishment of SRC was to arrest the challenge of widespread pay disparities, unsustainable wage bills, and politically motivated salary increments. The Commission’s role in harmonizing pay structures across the public sector was thus vital in restoring order and fairness.

The current standoff between University unions and the Ministry of education may not reflect the irrelevance of the SRC, but rather a weakness in its execution of its mandate and general coordination. As the framers of the Constitution of Kenya (2010) thought, fiscal prudence is critical, but it must go hand-in-hand with accuracy, consultation, and legitimacy. Since the figures released by the Commission in lecturers dispute appear inconsistent with the CBAs signed and registered, unions perceive SRC as attempting to rewrite contractual obligations.

The Problem of Data and Coordination

A key source of tension in this salaries dispute lies in data inconsistencies. It appears that SRC relies on macroeconomic models and aggregate payroll data, often submitted through the Ministry or the National Treasury. Universities on the hand operate with varied pay structures and records that are not always centrally updated. This mismatch produces divergent figures — and when released without prior joint verification, the resulting errors become politically explosive.

Moreover, the absence of a joint validation mechanism among the SRC, Ministry of Education, university councils, and unions creates a vacuum of trust. Once an advisory is issued unilaterally, even a minor computational error can be perceived as deliberate interference.

Unions and the Question of Credibility

The academic staff unions, for their part, were justified in refuting the SRC’s figures. Their refusal to accept faulty figures made the ministry to go back to the drawing table. The figures of Unions prevailed making the minister appear as someone without command over his data. However, this scenario brings forth the fact that for Unions confrontation alone may not secure lasting solutions. The future of union advocacy lies in technical strength. They must have the ability to challenge data with data. Evidence-based bargaining is the next frontier for Kenya’s labor movement, especially in the public sector. By investing in internal research capacity, unions can engage the SRC and Treasury on equal analytical footing.

Toward a Collaborative Framework

The crisis between the ministry of education and universities unions points to a deeper structural gap in the Kenyan labour relations: Kenya’s wage determination, especially in higher education, is fragmented across multiple institutions — the SRC (advisory), Ministry of Education (policy), Treasury (funding), universities (implementation), and unions (bargaining). Without a synchronized framework, disputes will persist.

A practical solution would be to establish a standing tripartite committee comprising the SRC, Ministry of Education, Treasury, university councils, and unions. This forum would serve as a technical validation and consultation platform for costing CBAs and monitoring implementation. Such collaboration would replace suspicion with transparency, ensuring fiscal discipline while honoring negotiated obligations.

Balancing Fiscal Control and Industrial Harmony

Industrial harmony is a necessity in Kenya. Specifically, the Kenya’s higher education system cannot thrive under perpetual industrial unrest. The SRC must remain firm on fiscal sustainability but flexible enough to engage constructively. Equally, unions must recognize the broader national context in their demands. Sustainable industrial peace will not emerge from confrontation but from shared responsibility and transparent dialogue.

Ultimately, as framed in our constition (2010), the question is not whether SRC should advise — it must. The question is how it should advise. SRC must endeavour to advise through participatory, data-verified, and transparent processes that build trust rather than hostility. When evidence replaces suspicion, and consultation replaces unilateralism, Kenya’s universities and other public education sector players, can move from pay disputes to academic excellence.

Author Bio

Dr. John Chegenye is a Human Resource Management scholar, educator, and consultant specializing in organizational behavior, labor relations, and performance management. He writes on leadership, labor policy, and institutional development.

Leave a comment